We Don't Believe Any Of This and We Don't Know Why

We can't think our way back into faith. We will need to live our way back in.

I recently read

’s new book, Living In Wonder: Finding Mystery and Meaning in a Secular Age, and could hardly put it down. Along the way, Dreher persuaded me that chatbots are the new ouija board, and inspired me to buy some Jesus Prayer beads. This is an excellent book. I think Catholics especially should read it.Last week, Dreher wrote that he had purchased John Vervaeke’s book Awakening From the Meaning Crisis after reading a tweet thread he wrote. The thread discussed the limitations of propositional knowledge (what we might call “beliefs”) in the modern world, in which the sacred has been hollowed out and all knowledge has been reduced to that which can be “abstracted, formalized, and universalized.” Here’s Vervaeke:

We are trying to live out the hunger for the sacred with only the tools of individual cognition and propositional belief—when what we truly needed is an ecology of practices—a living, interlocking system of disciplines, virtues, and communities that enact wisdom across multiple forms of knowing and being.

This is what the ancient traditions cultivated through rituals, contemplation, storytelling, and shared moral formation. These practices shaped consciousness, oriented attention, and transformed the self in relation to the world.

So you can’t think yourself back into sacredness. You have to live your way back into it.

I have never had much of an explicit interest in epistemology, but I am *adjusts glasses* reading Esther Meek’s Loving to Know: Covenant Epistemology with a group of women this summer, so the question of knowing is front-burner for me at the moment, and reading this thread from Vervaeke was enough for me, too, to order the Kindle version of his book and begin reading immediately. I’m only about a third of the way through it, but there’s so much to say already about this book, which is basically a transcript of Vervaeke’s YouTube lecture series surveying “the rise and fall of meaning in the West”.

Again, I have pretty much no background in epistemology, so the section in Awakening focused on Aristotle’s conformity theory, also known as “contact epistemology,” was an exciting discovery for me, especially in light of Dreher’s book, and Meek’s. To summarize, the conformity theory is the idea that we can only really know a thing (or a person) when we collide with it on its own terms and allow it to conform us (as the name suggests) to its contours. In short, it is “contact participatory knowing.” It’s the difference between looking at an anatomical sketch of a bird, and holding one in the palm of your hand. The difference between reading someone’s Hinge profile and kissing them goodnight.

As Vervaeke argues, this is an epistemology that acknowledges the human person is not a self-enclosed system but is always and necessarily in relationship with reality. The “world” we inhabit, in other words, shapes us, and shapes our beliefs about reality—and we, in turn, conform our actions and habits to that belief, reshaping our world in the process. There is a way in which, according to this account, we live in a kind of “I-thou” relationship with reality.

Modern epistemology, on the other hand, severs the connection between knowing and being, placing us in an existential mode in which knowledge is wed to having, to possessing, to dominating and imposing our will on reality. Instead of belonging to the world, we seek to control it.1

The tragedy here is that, because we cannot ultimately control reality (see: death), we are doomed to be perpetually frustrated when we live this way. We become imprisoned in a state of “modal confusion,” blind to the truth that peace cannot be found in control, but only in reciprocal belonging—in dialoguing with reality on its own terms. In this dialogue, we can experience “worldview attunement,” a “coupling and co-identification of agent and arena”; our understanding of the world begins to align with our actual lived experience, and vice versa, so that the two mutually reinforce one another. This reinforcement is the process by which we distill meaning from our lives.

Herein lies the trouble for Christians in the modern world. We are chronically modally confused. We believe (a.k.a. think) many things about reality (the Creed), but the world in which we live and move and have our being neither appears to accommodate those beliefs, nor does it reflect those beliefs back to us in a meaningful, sustained way. Here, I am not speaking only of the secularizing influence of the ambient culture, or even the re-paganization of secular culture that Christians are so fond of pointing out these days, real as both may be. Our own families, parishes, and communities are also subject to this modal confusion and fail to become zones of participatory contact with the Realities (God, Creation, the Incarnation, Redemption) at the heart of Christianity.

To say that Christians sometimes succumb to “worldly” ways of living is not saying enough; the true state of affairs is much worse than that. We are in the unenviable position of being trapped in a feedback loop that makes it increasingly difficult (dare I say impossible) to actually believe the things we believe. The mental scaffolding is simply not there. We have, as Vervaeke puts it, “reduced knowing to a single form: the knowledge that something is the case.” And so our life in the Church is reduced, too, to apologetics, doctrinal hair-splitting, and pious incantations. We fear, we doubt, we cry from the depths of our being, we need, and our knee-jerk response is to smother the discomfort with a syllogism. Little wonder it’s so hard to believe sometimes.

I like what Vervaeke offers here, though: what we do need is “an ecology of practices—a living, interlocking system of disciplines, virtues, and communities that enact wisdom across multiple forms of knowing and being.” A way of life. A habit of being. An incarnated communio with God and the Church. You and I, living in this existential hellscape (and, by the way, born for this very moment), should be on our knees daily begging the Lord to show us how to build this, to open our imaginations to what new forms of shared life could be possible if we would stop frittering away our precious lives on our smartphones or hand-wringing about the status of our 401(k).

What we need are modes of Christian living that make worldview attunement possible for ourselves and (please, God) our children. For example: we need, as

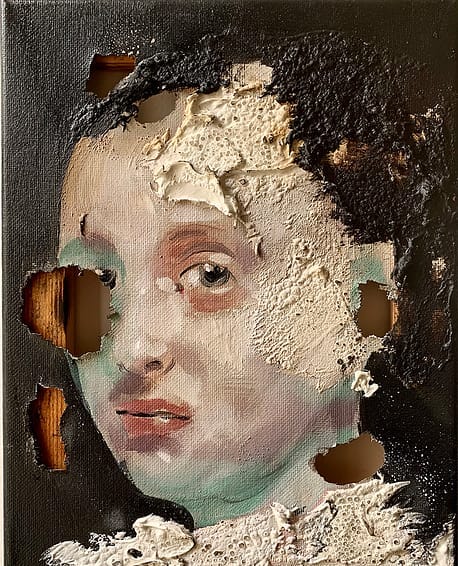

recently pointed out, to re-normalize intergenerational living and do away with our cultural obsession with the nuclear family. We need new educational institutions that foster curiosity and wonder and prioritize the student-teacher relationship. We need to loudly denounce competing messianic mythologies about the free market on the one hand and government intervention on the other, making room in our political and economic life for “activity carried out by subjects who freely choose to act according to principles other than those of pure profit” (Caritas in veritate, no. 37).Perhaps more than anything, we need to cultivate enchantment and encounter with beauty. Beauty disarms. It beckons. It calls forth our love. And significantly for our discussion here, it is what makes participatory knowledge possible, because only the beautiful draws us into communion. To quote the Beauty Dude himself,

In a world without beauty … the good also loses its attractiveness, the self-evidence of why it must be carried out. Man stands before the good and asks himself why it must be done and not rather its alternative, evil. For this, too, is a possibility, and even the more exciting one. Why not investigate Satan’s depths? In a world that no longer has enough confidence in itself to affirm the beautiful, the proofs of the truth have lost their cogency. In other words, syllogisms may still dutifully clatter away like rotary presses or computers which infallibly spew out an exact number of answers by the minute. But the logic of these answers is itself a mechanism which no longer captivates anyone. The very conclusions are no longer conclusive.2

Only along the way of beauty, by the witness of beautiful lives and beautiful relationships, will we attract rather than repel and make possible an authentic knowledge of God—maybe even start believing all of this for real.

If you are inclined to support the work I do here at Recovering Catholic, you can do so either by subscribing or by sending a tip via Buy Me A Coffee.

If you do choose to give financial support, thank you.

I can’t not say it at this point: this is just another way of articulating the “technocratic paradigm” that Pope Francis criticized so stridently throughout his pontificate.

Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord, vol. 1, Seeing the Form, 19.

So good. Doctrine rarely leads one to a relationship- of any kind. My husband and I saw an 200 year old carving of a rabbi in prayer and it stopped and silenced us - 35 years later we still remember the gasp out of our hearts!

Thanks again, Sarah, for a beautifully reflective piece. I have been moving ever closer to the conviction that faith is so much more than mere belief, and that faith springs from practice and not the other way around. I found this post inspiring, and I am ordering both Dreher and Meek’s books.