Catholic Deconstruction Is Having A Moment

Audrey Assad left Catholicism behind in 2018 after encountering the theology of Fr. Richard Rohr. Six years later, we're still talking about it.

This is Part I in a four-part series on Catholic deconstruction.

A sense of order is the easiest and most natural way to begin; it is a needed first “container.” But this structure is dangerous if we stay in its safe confines too long. It is small and self-serving. It doesn’t know the full picture, but it thinks it does. “Order” must be deconstructed by the trials and vagaries of life. We must go through a period of “disorder” to grow up.

Richard Rohr

When Joshua Harris, author of the 2003 book I Kissed Dating Goodbye (which he wrote at the ripe old age of 21), publicly announced in 2019 that he no longer considered himself a Christian, I don’t think I batted an eye.

When in the same year, the former lead singer of Hawk Nelson, Jon Steingard, posted on Instagram about how he no longer believed in God at all, I read the post, and felt sad. Sad for Steingard. Sad for those who had looked up to him in any way as a public representative of faith. I moved on.

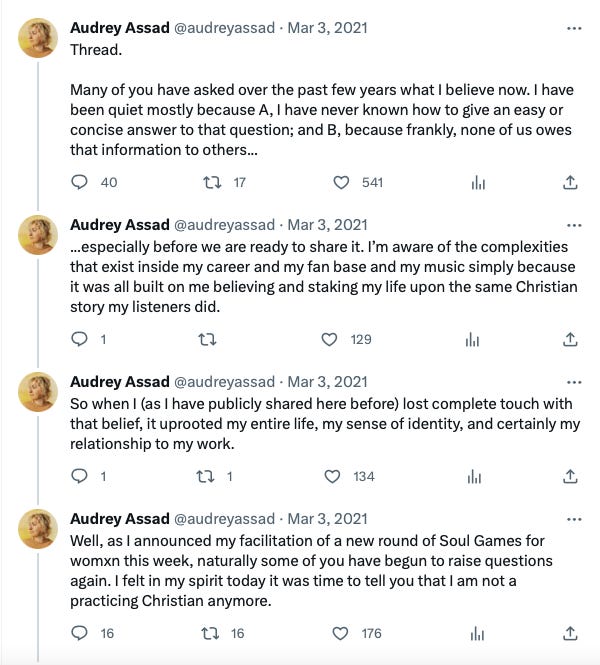

But when I read Audrey Assad’s Twitter thread explaining that she hadn’t been a practicing Catholic since around the release of her 2018 album Evergreen three years prior, it felt like a switch flipped in me.

At that point I had already witnessed many of my peers, alongside whom I had prayed, served, and grown in discipleship, “walk away” from the Catholic faith or Christianity altogether, a helpless and nonplussed bystander. Many of them were open about having experienced “religious trauma” or mental health problems as a direct result of their faith. Interestingly, these folks were not your average “cradle Catholics” who never saw the relevance of faith for their lives to begin with, but rather people who just months before, by all appearances, were on fire with the faith, living as deeply committed disciples.

So reading Assad’s communiqué in March 2021 felt like a watershed moment - the moment I realized that these were not isolated phenomena. Something bigger is happening in the Church. A large and growing number of young Catholics now describe themselves as “deconstructing.”

The popularized term “deconstruction” derives loosely from the work of Jacques Derrida, a twentieth-century French philosopher, who coined the term.1 When applied to faith (and this appears to be a phenomenon particular to Christianity), it signifies a process of critically examining the assumptions and foundations of one’s faith, sometimes resulting in a modified approach to that faith, but often leading to the complete rejection of faith altogether.

Catholics have enjoyed the benefit of a slight lag behind our Protestant and Evangelical brothers and sisters, for whom “deconstructing” has been a common coming-of-age experience for several decades (hence the large and growing number of self-professed “exvangelicals”)2, but it was inevitable that we too would have to reckon with the movement sooner or later; significantly, the controversial Catholic priest Richard Rohr is one of the leading voices in Christian deconstruction. Assad herself on multiple occasions has cited Rohr’s influence on her openness to deconstructing her faith.3

Fr. Rohr has been extremely popular and influential for decades, with loyal readers and devotees from all walks of life and faith backgrounds; in recent years he appeared as a guest on Oprah’s Super Soul Sunday podcast4 and his book The Universal Christ debuted at #12 on the New York Times Bestseller List5; Bono considers him to be a personal mentor. Needless to say, Rohr certainly appears to have a gift for reaching unbelievers, agnostics, and the “nones,”6 as well as those within his own tradition, presenting a spirituality palatable to them all.

But for someone who (at least implicitly) claims to hold and profess the Catholic doctrine of the Incarnation, he has come to some very oddball and troubling conclusions about the identity and mission of Jesus Christ.7 This matters. After all, it is Christ from whom we take the name “Christian;” he who is the object of our faith; he whom we seek in the Sacraments, in prayer, and in our Christian life; it is Christ who “fully reveals man to himself and makes his supreme calling clear” (Gaudium et spes, no. 22).

Additionally relevant is Rohr’s framework for spiritual growth and transformation, a “roadmap for deconstruction,” if you will, which he delineates into three “movements”: 1) order, 2) disorder, and 3) reorder.8 Permit me to quote at length from one of his Daily Meditations, in which he describes the dynamics of this process:

Only in the final “reorder” stage can darkness and light coexist, can paradox be okay. We are finally at home in the only world that ever existed. This is true and contemplative knowing. Here death is a part of life, failure is a part of victory, and imperfection is included in perfection. Opposites collide and unite; everything belongs.

We dare not get rid of our pain before we have learned what it has to teach us. Most of religion gives answers too quickly, dismisses pain too easily, and seeks to be distracted—to maintain some ideal order. So we must resist the instant fix and acknowledge ourselves as beginners to be open to true transformation. In the great spiritual traditions, the wounds to our ego are our teachers and are to be welcomed. They should be paid attention to, not denied or even perfectly resolved. How can a Christian look at the Crucified One and not understand this essential point?

The Resurrected Christ is the icon of reorder. Once we can learn to live in this third spacious place, neither fighting nor fleeing reality but holding the creative tension, we are in the spacious place of grace out of which all newness comes. God is now in charge, not us.

There is no direct flight from order to reorder. You must go through disorder, which is surely why Jesus dramatically and shockingly endured it on the cross. He knew we would all want to deny necessary suffering unless he made it overwhelmingly clear.

Let me start with what really resonates here: Rohr’s insight that the life of faith is not, as recent popes have pointed out, an algorithm for ready-made answers,9 a way to ensure that one is always right, a high wall to protect us from uncertainty, ambiguity, or doubt, seems completely faithful to both the Scriptural witness and the witness of the saints (consider, for example, the Dark Night of the Soul experienced by John of the Cross, Mother Teresa, and Therese of Lisieux). The Christian life, lived as it is in this world darkened by sin and concupiscence, inevitably contains within it an element of “unknowing,” to borrow a favorite word of Rohr’s.

“Rohr’s insight that the life of faith is not, as recent popes have pointed out, an algorithm for ready-made answers, a way to ensure that one is always right, a high wall to protect us from uncertainty, ambiguity, or doubt, seems completely faithful to both the Scriptural witness and the witness of the saints.”

Undue attachment to order and certainty chokes out the life of the soul; it is a way of shutting one’s eyes before the abyss of suffering and death that gapes before us - and though it shields us from the Bad News, we are also simultaneously blinded to the Good News. The Cross of Christ is then emptied of its power to really save us - not just from sadness, lack of direction, or bad habits, but from the existential anxiety and dread that every honest human being eventually needs to stare down.

So Rohr acknowledges that “disorder” is a stage in spiritual growth, and I agree. But how does one get to “reorder?”